- Home

- Books

- Women’s Rights

- Review

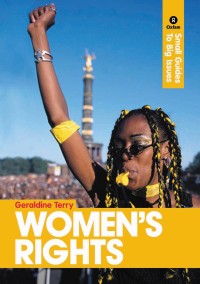

Women’s Rights

Women’s Rights is part of Oxfam’s “Small Guides to Big Issues,” a series of resource books designed for and written by people who are working to end poverty. Geraldine Terry is a British anti-poverty activist specializing in international development who has worked for NGOs (including Oxfam) as well as government-funded aid projects. Terry’s analysis is based on her experiences working with grassroots women’s groups in the Global South, in particular those who use the international conventions that protect women’s rights to empower women to fight poverty. The central premise of the book is that many of the most serious issues in the world today are “bound up with the denial and abuse of women’s human rights.” (3) International development programs continue to marginalize women’s rights, despite the fact that 60 to 70 percent of the world’s 1.1 billion poor people are women. This short volume explains how three decades of international development have been ineffective because they have not connected discrimination against women to child mortality, HIV/AIDS, lack of access to education and literacy, violence against women, and environmental sustainability. The book is not entirely pessimistic, though. Examples of successful local initiative that are based on rights-based approach to development demonstat4e that empowering women to change their own communities is often more effective than benevolent initiatives that only address immediate material needs. The book’s greatest strength is the focus on women in the global South as agents of change rather than beneficiaries of charitable development aid.

Focusing on rights rather than material needs changes the dominant image of poor women from “helpless charity cases” to “claimants of justice.”(17) The book begins with a critical analysis of the human rights framework, in particular the conventions that protect women’s rights. The key weaknesses of the human rights framework are the focus on political rights abuses in the public sphere, which occludes discrimination in the home, and its failure to change customs and traditions that assume that women’s subordination is the “natural state of affairs.” Even though the UN development policy includes goals and targets to improve women’s rights, many activist with whom Terry has worked feel that policy-makers merely pay lip service to women’s issues. For example, the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set 2015 as the target to eliminate poverty. But one sceptical activist call them the “Most Distracting Gimmick” (6) because gender equality is not the cornerstone of the policy. Terry identifies cultural relativism as one of the most significant threats to the universalism of human rights. Chapter 3 criticized opponents of gender equality who argue that women’s equality threatens traditional customs and values, and those who believe that human rights framework is a form of imperialism on the part of the global North. Terry argues that despite the shortcomings of international law, human rights conventions that defend women’s human rights, such as the Convention to Eliminate Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), must be defended because they resonate for women who are struggling to end poverty and to deal with the multiple issues that are associated with it.

Subsequent chapters elaborate on the interconnections between women’s rights and fundamentalism, voting rights, globalization, education, violence against women, HIV/AIDS, and new technologies. Property and inheritance rights are a consistent theme in each chapter. Women’s rights to property are restricted by law, convention, or traditions that were distorted under colonial rules. Dependency on male family members make it difficult, and in some cases impossible, for women to leave dangerous relationships or to acquire the education and skills that they need to move out of exploitative jobs. It is striking how many grassroots initiative to end poverty include women’s property rights as a fundamental goal.

Women’s stories are the heart of the book. Discussion of legislation designed to promote women’s rights initiates are juxtaposed with quotations by women whose lives have not been improved by these initiatives. These quotations reinforce the interconnectedness of women’s rights and the social issues related to poverty, as well as the need for rights-based development policy. More optimistic are the stories of women’s group that have changed ambivalence about violence against women, lobbied for legislation to end discrimination against women, organized programs to teach girl their rights, and establish centres to teach women skills that have helped them to live independent lives. These success stories demonstrate that small groups of women can make change. But they are tempered by the reminder that globalization, new technologies, and deregulation have created new challenges, and that more and more women live in poverty as a result of international trade agreements that put profit before human rights.

The goal of this series is to motivate readers to do something to combat poverty. The book concludes with practical recommendations to support rights-based development organizations as well as a guide to alternative media sources and websites that will help people to keep abreast of changes in women’s rights and local initiatives to end poverty. Students who are just beginning to learn about development should read this book because it explains complex issues and ideas in an accessible manner. Although those who are well-versed in human rights and international development may not learn much that is new, it is still worthwhile to read Women’s Rights because it is a powerful indictment of policies that maintain women’s poverty.

Nancy Janovicek

University of Calgary

Labour/Le Travail, Volume 63 (Spring 2009)