Beyond the Fragments in Interface

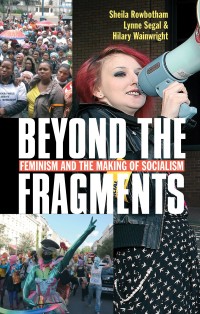

Beyond the Fragments

Feminism and the Making of Socialism

Beyond the fragments is one of those books that many activists cite as playing a role in their own biographies. I came across it in the mid-1990s, as a young organiser developing conversations and networks between different social movements in Ireland, in the overlap between European Green parties’ vanishing self-understanding as movement alliances and the first inklings of the Zapatista-inspired networking processes that would shortly lead to the “movement of movements”. We take our ideas and inspiration where we can find them, but read them critically, for what they can offer our own struggles and our own problems.

One of the liberating aspects of Beyond the fragments was that it embodied this kind of politics of knowledge. Rather than presenting a closed, seamless analysis with an agreed set of propositions which readers were implicitly encouraged to sign up to - the book as party conference motion - readers found themselves involved in a conversation between three activists who had come from different left organisations, with a range of related but not identical experiences in women’s, trade union and community organising. The open space created by this approach allowed readers to relate to the book as a conversation between their peers which they could join in.

This fitted with the picture presented by the book itself: rejecting the top-down political practice of Social Democracy, Trotskyism and orthodox Communism, it re-situated the authors, and activists in such parties, as participants in a wider conversation among a broader movement. That conversation was never liberal in form; it was always geared to practice and informed by a close discussion of specific experiences, but open to the possibility of making alliances between struggles without passing everything through the filter of organisational leaderships.

The book also embodied these experiences in its history: first published in 1979 by the Newcastle Socialist Centre and the Islington Community Press, two such examples of local, non-sectarian alliances between activists, it was taken up by Merlin Press, translated into several languages and fed into the development of what became known as socialist feminism, in the brief period before neoliberalism’s assault on socialism and its very selective alliance with elements of the feminist agenda reduced the space for that position to one of academic theory1. Now, after the experiences of the “movement of movements” and the new anti-austerity struggles, the book has been republished with substantial reflective essays by the three authors - each in the meantime widely respected as engaged thinkers by people from many different political spaces - looking back on the 1979 text, reflecting on its political context and the onslaught that was to come, and discussing the relevance of the questions raised by the book for today’s movements.

In her new piece, Sheila Rowbotham observes that it has to be recognised that the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s was part of a broader radicalisation. We had lived through a stormy decade of conflicts in workplaces and communities. In Ireland people were engaged in armed struggle. We had marched on massive trade union demonstrations, supported picket lines and learned from men and women on strike and in occupations. Then there were burgeoning movements against racism, around gay liberation. While our main focus in the decade before 1979 had been the women’s movement this did not mean we had been enclosed within it. (pp. 13-14)

In some ways, as all three authors note, we are returning to this kind of situation of movements and struggles overlapping with and informing each other - much to the discomfiture of NGO and trade union leaderships, celebrity activists and academic empire-builders whose local power is built on keeping “their” issue and “their” audience separate from others. To say this, though, is easier than to think through what it means; and much of Beyond the fragments then and now is about the three-way relationship between women’s struggles, working-class campaigns and political organisations large and small.

Reflecting on this question, Hilary Wainwright writes that

a more useful metaphor is to understand [political organisations] as part of a constellation - or, more mundanely perhaps, ‘network’ - of activities, sharing common values, involving all kinds of patterns of mutual influence, each autonomous but interrelated in different ways. Several further implications and questions follow. It becomes obvious that different ways of organising and different forms of democracy suit different purposes… Moreover, people sharing the values of this multiplicity of organisation and eager to be part of a process of social transformation will have different possibilities and inclinations to participate. A useful concept to capture a necessarily flexible approach to participation is ‘an ecology of participation’. (p. 56)

Again, and relevant to Interface as well as her own example of Red Pepper,

Rather than thinking in terms of unification versus fragmentation, I would emphasise a recognition of the necessity of diverse sources of power, and the need therefore to devise organisational forms for different purposes and contexts… This in turn points to the importance, as one piece in the organisational jigsaw puzzle, of a purposeful infrastructure to strengthen these flows of communication, cohesion and common political direction, with all the mutual learning that this involves. We all have to be activists and reflective observers at the same time. (61)

As she has explored in more detail elsewhere, Wainwright outlines the politics of knowledge involved in movement struggles, explorations of the possibility of a socialised economy and the possibility of “reclaiming the state” from below, as well as the vexed question of political parties in the process of transformation. She discusses the disappointments of previous attempts at movement parties such as die Grünen and Rifondazione comunista (p. 50) while arguing that political parties and an engagement with state power are nevertheless necessary, making particular reference to Syriza in Greece.

Part of the difficulty - and this is not to dismiss the strength of what she is saying - is that because of the centrality of the state to what we could call “common sense” popular politics (ideas shaped by nostalgia for the welfare state, national-developmentalism or state socialism) and the accumulation not only of power and financial resources but also of cultural prestige in the parliamentary arena and associated media, academic and NGO spheres, effective political parties tend to massively distort movement action.

Much like military strategies, they tend to wind up meaning that popular struggles put most, if not all, of their eggs in the state-centric basket, with the risks not only of generalising the cost of defeat in this arena but of the familiar ambiguous victory in which supposedly progressive parties wind up implementing neoliberal politics with the backing of movement forces who have invested too heavily in the party game to admit their mistake. “Good sense”, perhaps, would suggest a greater detachment from the fascination of the state and its Meaning - but of the many extraordinary experiments in Latin America over the past decade, few have managed to escape this logic entirely2.

One reason for this fascination, perhaps, has been the way in which neoliberalism has narrowed our imagination for what is possible and leads us to seek Meaning in a space which will not get us laughed at. Rowbotham again:

In the 1960s and ’70s, inspired by movements against imperialism, people of colour, women and gays imagined a politics of ‘liberation’ which went beyond rights, or access to resources. ‘Liberation’ suggested a transformation not simply of the circumstances of daily life but of being and relating. Instead of an individualism of selfishness and greed, there was to be self-definition and expression, instead of competition, association, trust and co-operation. This is the future I still envisage and want to help bring about. But I have to take a deeper breath before admitting to it. (p.25)

This sense of historical change and the contrast between what could then be taken for granted and what has, now, to be painfully rebuilt is powerful in Lynne Segal’s new essay:

When I turn back to that paradoxical moment, 1979… I know I am returning to another world. It is strange to revisit those times, when we were able to take so much for granted about commitments to direct democracy, equality and the need to develop and share the skills and imagination of everyone… The bottom line was the prefigurative politics that expressed our belief in mutual aid and the sharing of talent and resources (p. 93)

Segal’s contribution is deeply reflective, situating her libertarian left commitments in the late 1960s counter culture and their enrichment through the challenges she faced as a single mother in 1970s London, noting both the gains made by feminism in the decades which followed and the cost of growing class divisions to women and ethnic minorities in particular. Making the links between 1979 and Occupy, she is at once supportive, enthused and aware of complexities and difficulties to come:

Drawing especially upon the impact of feminism, the problem as we saw it back then was how to facilitate more dialogue and co-operation between the different organized left groups and diverse activist movements to build coalitions solid enough to confront the triumph of the right under Margaret Thatcher. In so many ways we seem back in that moment again, except that the obstacles we face have grown formidably. (p. 66)

If ever a movement embodied William Morris’s comments about the ambiguity of popular struggle, it was surely second-wave feminism:

“I pondered all these things, and how [people] fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other [people] have to fight for what they meant under another name…”

What liberal feminist, in 1960, could have predicted that so many legal barriers to gender equality could fall, that so many educational changes could be brought about, and that economic inequality would remain so marked, while patriarchal forms of popular culture would experience such a revival? What radical feminist in the same period could have imagined the bulk of their movement turned into service provision in state-supported work on rape and domestic violence, with so many battles won around contraception, divorce and (albeit still contested) abortion - and that rape culture could be so aggressive and so public at the same time, while women’s control over their own bodies in childbirth would remain such a marginal issue? What Marxist feminist could have conceived that women’s role in paid labour could undergo such a transformation and yet the cultural power of marriage and family remain so strong?

In all these cases, the genre which seeks to identify first causes, locate strategic issues and propose theoretical analyses dates quickly, and for a simple reason: it relies on the exclusion of the richer complexities of present-day struggle, and substitutes individual analysis for collective practice. Similar gestures had long been dominant in statist left politics, and the original essays challenge these from many directions, rejecting not only social democratic technocracy and the de facto conservatism of British Communism but equally the self-proclaimed wisdom of Trotskyist leaderships - above all, the practice of domination by small male elites, the silencing of dissent, the instrumental approach to movements and the dismissal of popular experience. Then as now, the book’s openness, conversational tone and refusal of the seamless analysis inviting either submission or departure are very welcome:

every form of subordination suppresses vital understandings which can only be fully achieved and communicated through the liberation of the oppressed group itself. No ‘vanguard’ organization can truly anticipate these understandings… If a revolutionary movement is to be truly able to encourage, develop and guide the self-activity and the organized power of the oppressed then it must be able to learn from and contribute to these understandings… To a very large extent socialist politics should derive and at times, has derived, its main content from these understandings. (Wainwright in 1979; p. 113)

Unlike many classics from its time which remain on reading lists, the original Beyond the fragments does not focus on structural analysis, hypothesised genealogies of patriarchy or polemics directed at other feminists. Instead it presents us with the question of how we can learn from each other’s struggles: how feminists, community activists, radical trade unionists and others had learned to organise; how this contrasted with the logics of social democracy and Leninism; and how a conversation between these experiences of popular self-organisation might look.

This practical emphasis, of course, takes it away from the format preferred by the university, today far and away the single largest institutions socialising people into explicitly feminist identities; however, it takes it into the heart of actual organising. Segal’s 1979 essay closes, appropriately, with a statement of problems for movement practice:

First, the relationship between feminism and personal politics, and left groups and the general political situation. Secondly, the relation between local organizing and national organizing, and how this relates to the conflict between libertarians and feminists and the traditional left in the current situation. Thirdly, how we move on to a perspective for building socialism which can incorporate both feminist politics and the new ideas and ways of organizing which have emerged over the last ten years. (p. 279)

That some of these might now seem like dead issues at first glance of course reflects the extent to which we have become institutionalised or - to put it more harshly - succumbed to the neo-liberal logic of fragmentation in which we find quick, dismissive answers to the big questions and invest ever more heavily in our own special areas of interest and our own “niche markets”.

The original essays in Beyond the fragments, written at the end of a decade of women’s, gay / lesbian, migrant and working-class struggles and campaigns over issues such as nuclear power and the Vietnam war, show the extent to which these different movements were then intertwined, learning from one another, exploring similar issues and registering similar ambiguities and contradictions - an experience which found shape in formations such as socialist feminism, eco-socialism, black feminism, and other attempts to rethink and reformulate the hard-won knowledge of popular struggles in ways that brought together something at least of a shared analysis of causation and structure as well as some parallel directions in struggle, organisation and goals.

Those moments were broken apart, not only by neoliberalism but also by empire-building strategies on the part of organisational leaderships, movement intellectuals trying to create space in the academy and celebrity authors converting movement into commodity. We have spent much of the last fifteen years or so trying to piece the fragments together one more time: more cautiously perhaps, aware of the long history of mutual distrust and origin myths which sanctify our specific identities (including, it should be said, socialist ones) as against others.

As we have done so, we have found ourselves reclaiming, recycling and reusing much of that earlier movement knowledge in our own contexts, talking through forms of structural and historical analysis which do not privilege a single struggle, exploring alliance- and network-based strategies for change and discussing forms of social organisation which would not rest on exploitation and oppression in any dimension, and trying to go further:

You need changes now in how people can experience relationships in which we can both express our power and struggle against domination in all its forms. A socialist movement must help us find a way to meet person to person - an inward as well as an external equality. It must be a place where we can really learn from one another without deference or resentment…

This means a conscious legitimation within the theory and practice of socialism of all those aspects of our experience which are so easily denied because they go against the grain of how we learn to feel and think in capitalism. All those feelings of love and creativity, imagination and wisdom which are negated, jostled and bruised within the relationships which dominate in capitalism are nonetheless there, our gifts to the new life. (Rowbotham in 1979; p. 232/9

This is there, too, in both sets of essays in this book: the authors share, in different ways, the experiences, choices, mistakes and learning which underlie and give rise to particular formulations, strategies and problems - and in so doing enable the reader, too, to position themselves as another such activist, struggling with the problems they encounter and trying at the same time to go beyond them.

In the wake of the “movement of movements”, the alliance-building experiences of Latin America and the broad popular participation in anti-austerity movements in Europe, the new Beyond the fragments offers precious resources, calm voices grounded in experience and the long perspective of present-day activists reflecting on past struggles. It will be a valuable contribution to “the movement” - which will be feminist, and anti-capitalist, and many other things too, if it is to change the world.

–Laurence Cox

Interface Vol 5(2), 525-559, Nov. 2013