The Outsider

Nick Ternette was Winnipeg’s Public Radical No. 1 for more than four decades, yet very few people understood who he was and what made him tick.

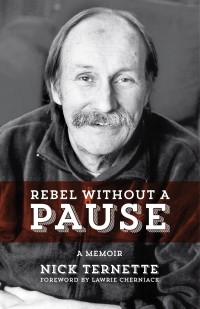

In Rebel without a Pause, his posthumous memoir modestly produced by a left-wing publishing house, Ternette fills in the blanks with a portrait that is both interesting and entertaining, if not entirely flattering.

By the time he died last March at age 68, Ternette believed he hadn’t accomplished much in his life, but he had no regrets. He was also aware mainstream politicians never took him seriously, even if they tolerated his presence.

That’s why no one was more surprised than he when the Winnipeg establishment, including some who loathed his socialist hectoring, responded with kindness and generosity in 2009 when he lost his legs to flesh-eating disease following complications with cancer.

The University of Winnipeg, which evicted him during one of the 400 demonstrations he organized or attended in his life, named him a distinguished alumnus and offered him a two-bedroom suite at the student residence for him and his wife, Emily.

Donations were made to charities in his name, people stopped him in the street, hugged him and thanked him for his service. Former mayor Susan Thompson, with whom he quarrelled endlessly, called him “a historic figure” who should have a park named after him. A trust fund established to help the couple cope quickly swelled to $30,000.

The accolades went on and on, and accelerated after his death.

Bullhorn Nick, as he was known, was baffled by it all because “truth be told, I had not accomplished that much in Winnipeg.”

There were a few victories, such as the work he did with a young Greg Selinger in 1971 in setting up a free income tax service for the poor, but “they were few and far between.”

Many young people in the 1960s held radical left-wing views, but as Ternette himself says, most of them eventually moderated their opinions and got on with their lives.

But not Ternette. He was a Marxist Peter Pan trapped in his own Neverland of ideology and public protest against the pirates of capitalism.

He sometimes stretched his principles to the point of absurdity, such as when he turned down a job with the Mennonite Central Committee because he wouldn’t admit to being a pacifist, a condition of employment. In his view, no one who participates in “the violent system of capitalism” can be a pacifist.

He laments the decline of 1960s-style radicalism – “then you were part of a generation. Now, you are just a wacko” – but, in fact, there is a new generation of activism expressed in the environmental movement, the occupy movement, anti-globalization and aboriginal militancy.

Ternette, of course, supported all these groups, but from a Marxist point of view. For him, nothing would ever improve until the state withered away and there were no more capitalists.

His single-minded commitment to radicalism and endless protesting, combined with eccentric personal behaviour, doomed him to poverty and ridicule, but he didn’t care. The pursuit of a just and equal society, and the end of capitalism, was all that mattered to him.

Ternette was aware from an early age something was wrong with him. He says he may have suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder or, possibly, Asperger syndrome.

He traces his personal problems – he was often in therapy, including Freudian psychoanalysis – to a difficult childhood that left him unable to experience or demonstrate intimacy.

The only child of a loveless marriage, Ternette grew up in Berlin during the Second World War. His mother was born in Turkey of Russian nobility, while his father was also Russian and served as an interpreter for the German army in Russia, where he was captured and held in prison until 1948.

His mother was a painter, but her only portrait of her son presented him as “totally asymmetrical, almost hideous, and I am left to wonder about that the rest of my life.”

For the first 10 years of his life in Germany, he was hated as a Russian. When the family moved to Winnipeg, he was despised as a Nazi because of the German accent he, strangely, never lost.

As a boy, he wanted to fit in, but he ended up the perpetual outsider.

Winnipeggers who knew Ternette will find Rebel Without a Pause a fascinating read, if occasionally disjointed, and it also has some interesting observations about the city’s left-wing fringe and the amazing array of radical groups in the ’60s and ’70s.

Ternette knew them all, including the Black Panthers, and he even stormed the streets in Germany during the student riots of the late 1960s.

There are many well-told stories and anecdotes, such as the $500 payment (bribe?) he accepted not to run against Ralph Klein in his first bid for the mayor’s job in Calgary – where he lived briefly in the early 1980s – or the time he visited then premier Ed Schreyer in his home on Christmas Eve with a petition wrapped as a present.

Ternette may not have understood the affection he was shown at the end of his life, but there is no doubt it was real. And while he questioned his own importance, he served for decades as a faithful watchdog and provided a voice and forum for those, like himself, who felt marginalized and ignored.

Bullhorn Nick was a Winnipeg original, the city’s last full-time radical. Politics in the city just isn’t the same without him.

– David O’Brien is a member of the Free Press editorial board.

Republished from the Winnipeg Free Press print edition November 2, 2013