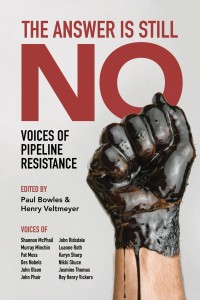

Review of The Answer Is Still No

The Answer Is Still No

Voices of Pipeline Resistance

The Northern Gateway pipeline is just one of several major pipelines proposed to transport tar sands bitumen from Alberta to non-American markets, in this case to Asian markets via the port of Kitimat on British Columbia’s northwest coast. The tremendous opposition to Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline expressed during the recent Joint Review Panel process intrigued two professors, Paul Bowles and Henry Veltmeyer, who then set out to understand the pipeline resistance movement. They travelled east to west in B.C., from Prince George to Prince Rupert, interviewing key activists and community members along the proposed pipeline path. The Answer Is Still No is the result of those conversations. It provides evidence for the provocative claim by Bowles and Veltmeyer that despite the Harper government’s unambiguous support for pipeline projects and the corporate pressure to see them completed, “there is one certainty: the Enbridge pipeline will never be built.” Why? Because “the people of northern British Columbia and their supporters elsewhere will not let it happen”; because the “depth and breadth” (7) of resistance to the pipeline is so widespread.

The collection of interview transcripts is bookended by an introduction and afterward by Bowles and Veltmeyer drawing on their combined expertise in economics and international studies. The ten chapters in the body of the volume include conversations with twelve people representing a wide range of communities and groups pushing back against the pipeline. For example, the interview with Jasmine Thomas from the Saik’uz First Nation captures the perspective of the work of indigenous organizations to protect the Fraser River watershed. Thomas emphasizes the scope and diversity of strategies used by First Nations, from lobbying for changes to the federal government’s review processes, to raising awareness at shareholder meetings of Canadian banks, to learning from the experiences of communities confronting the negative impacts of oil projects in Ecuador and the Gulf of Mexico. Thomas also describes how First Nations women have led this resistance from the “grassroots”—she described “anti-Enbridge headquarters” as being “four of us women sitting in a living room” (37)—and underscores the important relationship between First Nations communities and non-governmental organizations, one that requires the recognition of First Nations’ leadership and sovereignty.

In a subsequent chapter, John Ridsdale, Chief of the Tsayu Clan and natural resource coordinator at the Natural Resource Department of the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, describes the attempts by pipeline companies to gain consent for their projects (for example, by dividing First Nations communities and avoiding a cumulative analysis of projects), and how the federal government has supported extraction projects through regulatory changes (such as retreating from protecting the vast majority of Canadian lakes). Ridsdale contrasts the tunnel vision and short-sightedness of corporations and government with his community’s awareness of the full scope of the pipeline’s potential impact and long term commitment to protecting these lands and waterways. Ridsdale also reflects on how this pipeline debate is unifying First Nations communities, non-governmental organizations, recreational fishers, and people working in the agriculture, forestry, and commercial fishing sectors: “we wanted to thank Enbridge for bringing us so tightly together,” he comments. “Enbridge did us a favour. For them to bring us together like that was amazing” (60).

The interview with Nikki Skuce of ForestEthics provides another window into the pipeline resistance from the perspective of major environmental organizations. Skuce draws attention to how organizations resisting this pipeline have learned from the experience of opposing other extractive projects in the region. The most recent debate on coalbed methane, for example, taught activists the value of creative, multi-pronged strategies of resistance using a blend of organizing public debates and information sessions, pressuring the corporation at international board meetings, supporting concerned municipalities, lobbying governments, and undertaking direct action. In the Enbridge pipeline case, Skuce credits First Nations communities with leading the resistance and underscores the importance of northern community organizations in leading the non-First Nations community effort (as opposed to national and international environmental organizations from outside the region). Skuce reflects on the “synergistic” (83) relationship between ENGOs and First Nations communities, observing that while there are often divergences of opinion and sometimes conflict, overall there is cooperation. Successful resistance to other projects has built a sense of “empowerment”: “we know we can stand up together and win” (85), she notes.

Bowles and Veltmeyer let the interviewees’ words stand for themselves in these edited transcripts. The result is a number of unique and broad-ranging conversations. (This is certainly an unconventional publication from two university professor. Readers seeking a more traditional academic analysis should pair the book with Bowles and Veltmeyer’s 2014 article, “Extractivist Resistance: The Case of the Enbridge Oil Pipeline Project in Northern British Columbia.”) And these voices need to be heard now more than ever as the debate over this pipeline and related projects intensifies.

Three months after The Answer Is Still No was published, the federal Cabinet approved the project, subject to the 209 conditions of the National Energy Board’s Joint Review Panel. Enbridge maintains it will start pipeline construction in 2016, moving oil by 2019. However, legal challenges against the project are mounting. As of this writing, nineteen lawsuits have been filed against the project involving First Nations communities—emboldened by the recent Supreme Court of Canada decision to grant aboriginal title to the Tsilhqot’in First Nation—as well as environmental and labour groups. Public support has also grown for the NDP private member’s bill to ban tankers on B.C.’s north coast. Meanwhile other major pipelines proposed to move bitumen west, east, and south have been met with protest, civil disobedience, and lawsuits. The oil price plunge might lessen the pressure for more pipeline capacity, but this will be momentary at best: industry and federal government officials continue to stress that the Northern Gateway pipeline is still needed.

The Answer Is Still No provides a historically informed, on-the-ground view of the movement resisting this project. It offers practical insights on how groups involved in this struggle are framing the issue, inventing alternatives, as well as building and maintaining coalitions of unlikely allies. The book also provides something much needed in Canadian debates on oil and gas: optimism that First Nations communities joined with a broad range of NGOs and local governments can confront what sometimes appears to be a monolithic wall of government and corporate consensus on extractivist projects.

— Angela V. Carter is an assistant professor at the University of Waterloo